People with von Willebrand disease have defects in the process that controls blood coagulation. This is usually caused by mutations in the von Willebrand factor gene that either result in reduced levels of Von Willebrand factor in blood, or a variant of von Willebrand factor with abnormal function. Because von Willebrand factor plays a crucial role in blood coagulation, von Willebrand disease patients suffer from frequent and excessive bleeding.

In about 20 per cent of people with von Willebrand disease, something strange is going on. These patients have reduced levels of von Willebrand factor in their blood, but they do not have mutations in their the Von Willebrand factor gene, which means that there must be another cause for their disease. ‘We have been looking for years to find what causes the disease in these people’, says Erasmus MC hematologist Prof Frank Leebeek. A recent study by the department of Hematology, published in Blood, now points to a new cause.

Cascade of proteins

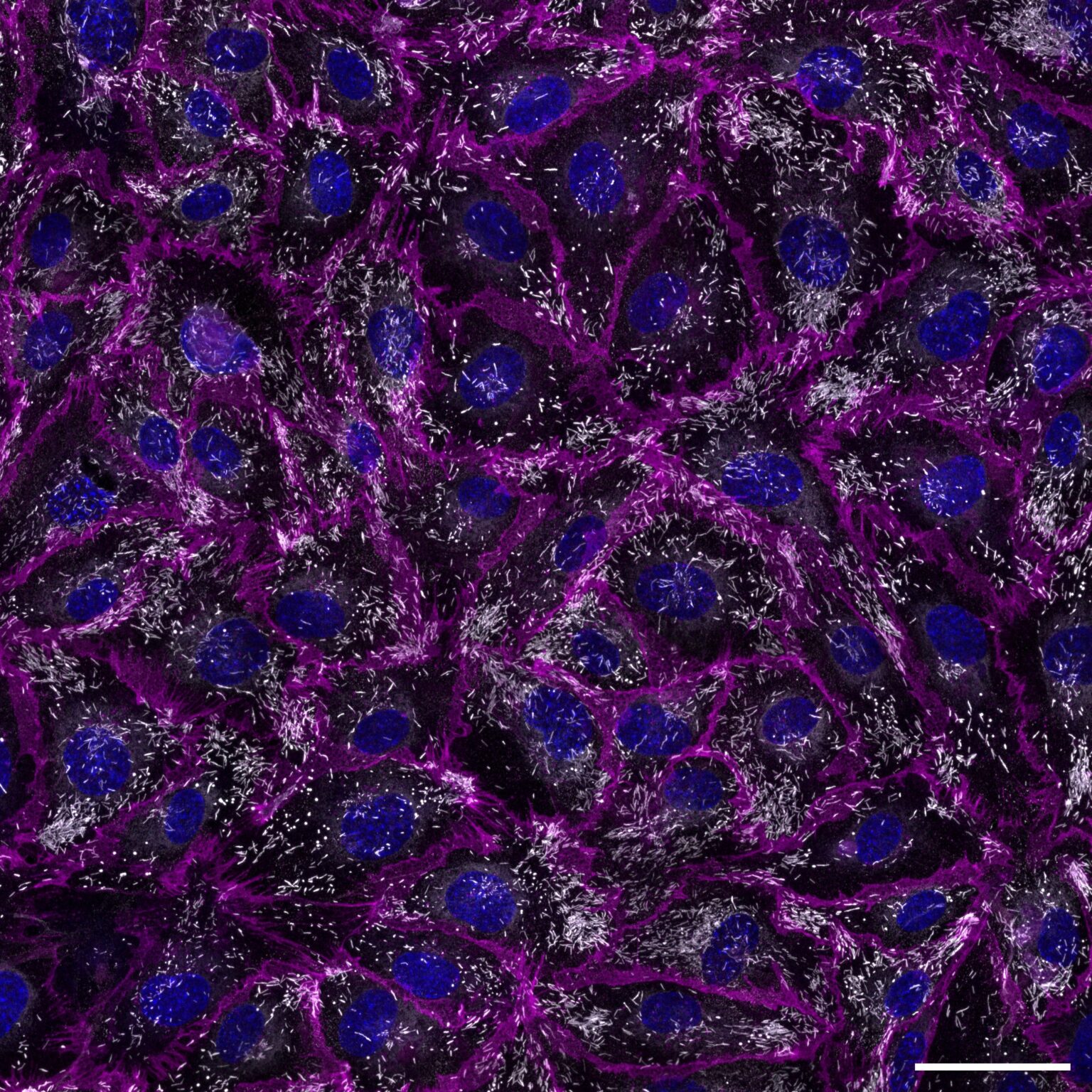

Not only problems with the clotting protein itself, but also its secretion from the blood vessel wall appears to be able to cause von Willebrand disease. The endothelial cells that form the inner lining of blood vessels contain specific storage organelles in which the von Willebrand factor is stored, the so-called Weibel-Palade bodies. Once a blood vessel gets damaged and bleeding needs to be stopped, a cascade of other proteins come into action, which together ensure that von Willebrand factor from the Weibel-Palade bodies gets secreted into the blood.

If something goes wrong in that process, this can also lead to insufficient von Willebrand factor in the blood and clotting problems, researchers led by Dr Ruben Bierings of the Department of Hematology now show.

Endothelial cells with the cell membrane in purple, the cell nucleus in blue and the Weibel-Palade bodies containing Von Willebrand factor in white.

This is an important discovery for hematologists, Leebeek explains. ‘If we understand where the disease comes from, we can treat it better. The preferred treatment for von Willebrand disease is to temporarily raise the levels of Von Willebrand factor in blood using a drug that stimulates the secretion of von Willebrand factor from the endothelial cells of the patient. However, in patients with defects in the secretion process this will not work and such treatment is unlikely to be useful. Then we have to switch to another type of treatment.’

Special group of patients

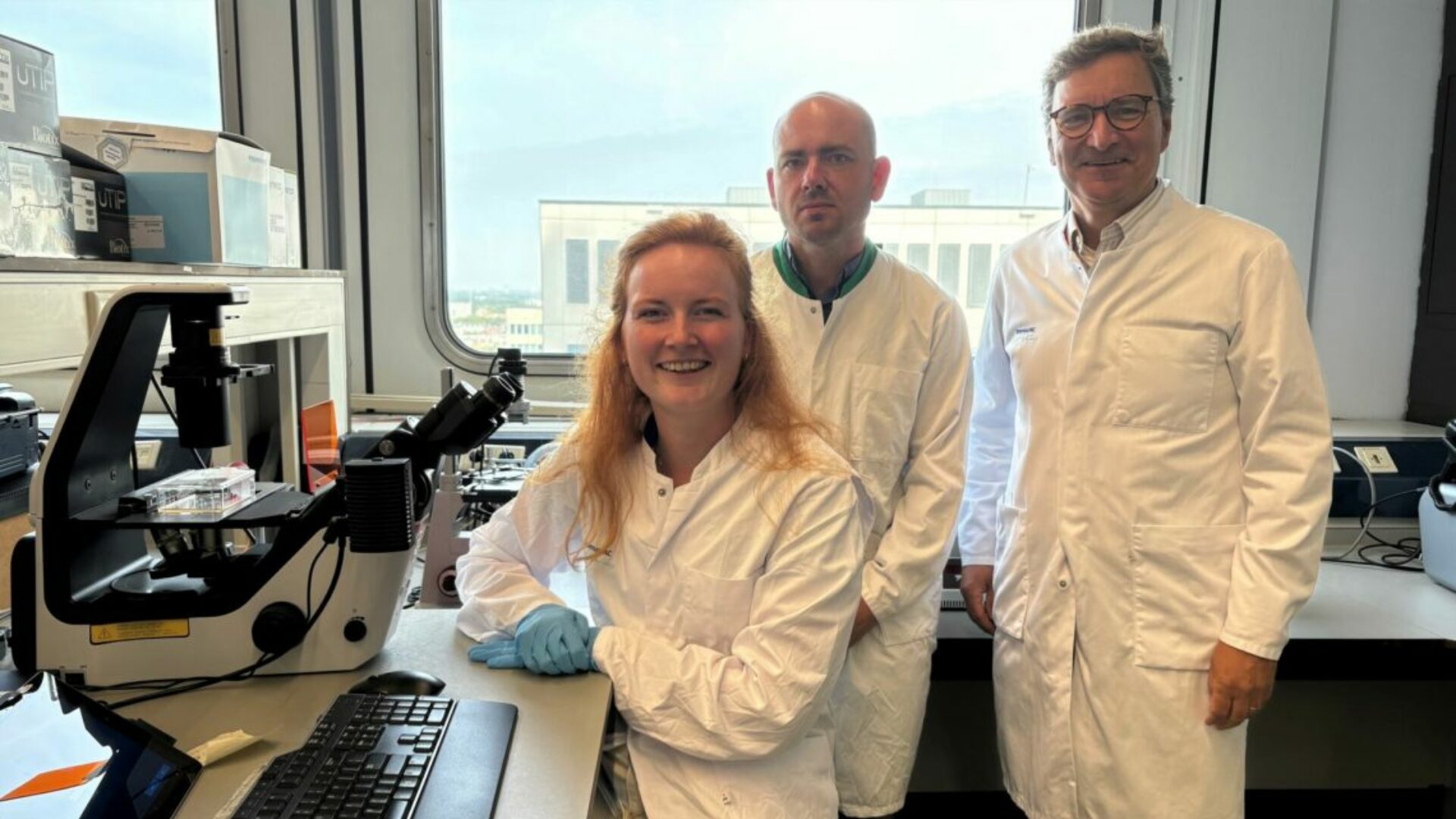

The trail to the discovery ran through a special group of patients: people with a mutation in the MADD gene. ‘Only 26 patients are known worldwide and thanks to the help of pediatricians from the Czech Republic, Germany and Belgium we were able to include three of them in our study,’ says PhD student Sophie Hordijk. ‘From earlier research from our group we already suspected that the MADD protein is important for the secretion of von Willebrand factor in the blood. So in theory, these patients should also have clotting problems. Now, through blood measurements and experiments with cells from these three unrelated patients, we show for the first time that this is indeed how it works in the body’, Hordijk explains.

A crucial part of this study involved live imaging of the secretion process of Weibel-Palade bodies in patient cells, for which Sophie had to use a specialized microscope at St George’s University in London. The study also involved collaboration with scientists at Sanquin in Amsterdam, among others.

Sophie Hordijk in London, live imaging the secretion of Von Willebrand factor from MADD patient cells.

Because of the rarity of the mutation, MADD patients probably explain only a small proportion of the 20 per cent of patients with von Willebrand disease without an identifiable cause. Yet this could be the start of more diagnoses, Hordijk believes. ‘This broadens our view. We can now look more specifically for mutations in other proteins involved in Von Willebrand factor secretion.’

Biomedical research

Through biomedical research, we work to understand basic biological and medical principles. This research is at the heart of medical progress and lays the foundation for innovations that improve care. As stated in Strategy28, Erasmus MC’s strategic plan.